Some of my favorite things…

Time to dig into the past. Before I go too far, a recap of the sort of records that exist out there is in order. Though many primary source documents are just a few clicks of the keyboard away, nothing replaces a trip to a city or town hall, a state or judicial archive, or a library.

And why?

Because often computers (surprise) make mistakes when deciphering handwritten records. For example, it might interpret the given name “Eliphalet,” as Elizabeth. So, if it’s accuracy you’re looking for, it’s off to the archives.

Some of the primary source records out there include census records, court records, church records, newspapers, city directories, land records, police records, vital records, and of course, probate records.

Some of the primary source records out there include census records, court records, church records, newspapers, city directories, land records, police records, vital records, and of course, probate records.

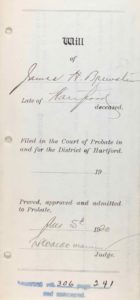

Ah, probate records (dreamy sigh…)

Probate records are a persons decision regarding the distribution of their estate, including such things as bonds, accounts, inventories, petitions, administrations, orders, decrees, and distributions.

Now if you’re thinking that no one ever looks at the early colonial or nineteenth century wills or wills in general. Think again. Lots and lots of scholars pour over these documents. Generally speaking, they use them for things like a thesis or a weighty dull academic tome. Often, they are examining them for raw data, like how many men favored their sons over their daughter, or how the deceased male manipulated his first or second wife, by stipulating all inheritance left to the merry widow would revert to a son or daughter should she remarry, or suspicious sums of money left to a loyal secretary or dedicated chauffeur. You get the idea.

Making a will is a person’s last identity pronouncement. It is a person’s last wish and their last attempt to impose their will on the living. And that my friend is when it gets interesting.

During the colonial period and into the nineteenth century, justice was swift. So too was the probating of a will, which was generally accomplished within a year of a person’s death. After all, the living had to… well, make a living.

So what’s in these documents for the writer of historical fiction? Lots of juicy tidbits that make a good story come alive with authenticity.

Long before the internet, C.S. Forester of the Hornblower series stumbled into a book store and bought three volumes of the Naval Chronicles —a magazine published between 1790 and 1820 — by naval officers for naval officers. And, you might ask, what does that have do with wills? Well, this is a good example of primary source information (let’s not quibble about primary vs. secondary), unfiltered by nosey historians looking for a paper trail to support some theory or another. It was raw. It was first hand. And was chalk-full of artifacts from the past, in written form. Forester read and re-read those volumes and immersed himself in the attitude of the day to the point where he breathed the same salty stale air, translating it all into a fictionalized and very successful series of books, which are still read today. Many fans enjoy his rich detail (It’s light on sex.) which only come from deep emersion into the subject.

But I digressed.

Back to wills. What can you expect to find in a will?

Back to wills. What can you expect to find in a will?

An inventory to start.

Here’s the kind of living artifacts that can be discovered in a will right down to the color, size, quality, and sometimes even, the condition of the things to be willed:

Livestock (horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, chicken, poultry, etc..)

Food stores (bushels of corn, wheat, rye, pickled beef, hogsheads, etc.}

Real property (acres of land, houses, barns, out buildings, grist mills, cider mills, blacksmith shops, etc.)

Personal property (household furnishings, as in sheets, quilts, pots and pans, tools, and slaves. Wait. What? That’s right. Many New England farmers, merchants, and landed gentry owned at least one or two domestic slaves. And yes, the probate appraiser placed a value on them, and passed them right down to their sons or daughter. It’s a secret New Englanders seem unaware of today. Who do you think built many of those lovely stone walls we see everywhere in New England?)

And then, there are those protection clauses (use of rooms in the house, use of a horse, use of food stores, use the family pew in church, care in sickness and in death for that pesky second wife… or sick father-in-law…etc.)

What does all of this have to do with historical fiction?

Wills provide us with one of the greatest insights into past behavior. Like the archaeologist who reconstructs hunting and gathering behavior from a shard or bone fragment or the remnants of an ancient fire pit, you can make reasonable assumptions about behavior, imperfect as it may be. And why undertake such a mission into the dusty archives?

Well, for the hope of discovery. For the unexpected surprise. Because as Paul Ricoeur writes, “History only emerges after the game has already been played.”

No Comments